Review

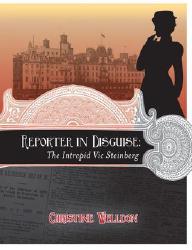

Reporter in Disguise

- Christine Welldon

- Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 2013

In contemporary Canadian society, we are struggling with the viability of newspapers. Arguably everyone wants news, but in the age of the internet, few people want to pay for it. At the same time, we are questioning the purpose of journalism: does it provide the foundation of democratic society, holding the privileged and the powerful to account? Does it uphold the status quo on behalf of powerful interests? Or is it just one more form of media entertainment? The profession of journalist is vexed as it has not been before, yet students continue to train to work as reporters, editors, and correspondents, to ensure that the stories of the people and their institutions are widely — and, we hope, accurately — told.

A little more than a century ago, the profession of journalist was just becoming established, and some women wanted to be reporters, an avenue that was closed to respectable women (although it was somewhat more acceptable for middle-class women to write for women’s magazines about domestic topics). Reporter in Disguise: The Intrepid Vic Steinberg tries to discover the identity of one woman who made it as a reporter in the late nineteenth century: Canada’s own Nellie Bly, Vic Steinberg. Steinberg (whose real identity remains unknown) was not a stunt journalist like Nellie Bly but rather considered herself an investigative reporter. Certainly, in the quotations from Steinberg’s published columns we may perceive a women questioning and resisting her society’s norms around gender, religion, class, poverty, and privilege.

Author Christine Welldon explores who Vic Steinberg might have been through a series of chapters that recreate Steinberg’s undercover assignments; each chapter ends with a prompt encouraging readers to reflect critically on what the episode has suggested about Steinberg’s identity. We see Steinberg in a variety of personas, from dressing as a man to sit in a pub to disguising herself to work as a domestic servant to impersonating a fortune-telling to examine how easily people’s hopes and dreams may be manipulated. The mystery of how Steinberg maintained this secret identity is engaging but may also seem abstractly quaint to contemporary readers. It may be difficult, for instance, to imagine a world in which a woman attending a rugby game would be shocking and unheard of, or to understand the class distinctions between a shop girl at Eaton’s and the clientele she served.

Overall, the reconstruction of this mysterious persona is effective, but I would have liked the author to take the investigation deeper. There is unevenness in the presentation that limits the accomplishment of the text; for instance, issues of religious discrimination are referred to in passing but are not developed, despite that Steinberg clearly had strong opinions about organized religion and, as another reviewer has observed, that Steinberg’s last name may suggest something about her identity. Steinberg’s commentary about economics and privilege also deserves further critical reflection, particularly given the nineteenth-century context. The book’s artwork is also somewhat puzzling, a mixture of period images and current illustrations that produces an inconsistent representation of Victorian Toronto. Still, I hope the text will encourage students, male and female, to be excited about journalism and its role as a noble profession — and even to want to pursue this work themselves in the future.

This review was originally published in Resource Links on October 2013.